Iran In 1930: A Nation Forged In Modernity And Turmoil

Table of Contents

- The Dawn of a New Era: Persia Becomes Iran

- Reza Shah's Vision: Modernization and Infrastructure

- A German Connection: Opportunity and Influence

- Unveiling Society: Cultural Transformations

- Echoes from the Earth: The 1930 Earthquake

- Unearthing History: Archaeological Endeavors

- Industry and Innovation: A Nascent Industrial Scene

- Legacy of a Pivotal Decade: 1930s Iran

The Dawn of a New Era: Persia Becomes Iran

The early 1930s were a period of intense national identity building for Iran. While the Pahlavi dynasty had formally begun with the crowning of Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1925, the symbolic shift from "Persia" to "Iran" gained official momentum around this time. Prior to 1930, the nation was largely known to the Western world as the "Imperial State of Persia." However, the Pahlavi government, keen on emphasizing the indigenous name of the country – "Iran" – which has ancient roots and means "Land of the Aryans," began a concerted effort to promote its use internationally. This renaming was more than a mere change of nomenclature; it was a deliberate act of asserting national sovereignty and cultural distinctiveness on the global stage. It reflected Reza Shah's broader vision of a modern, unified, and proud nation, shedding the historical baggage associated with the Qajar era and embracing a forward-looking identity. This pivotal moment set the tone for the transformative decade that was **1930 Iran** and beyond. The shift was part of a larger nationalist project, aiming to consolidate power, centralize governance, and foster a sense of shared destiny among its diverse populace.Reza Shah's Vision: Modernization and Infrastructure

Reza Shah's reign (1925-1979, though his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi continued until 1979) was characterized by an ambitious drive for modernization, and the 1930s were arguably the height of these reforms. Between 1930 and 1941, Iran embarked on an unprecedented series of infrastructure projects designed to bring the country into the modern age. These initiatives were not merely about convenience; they were strategic endeavors aimed at strengthening the central government's control, facilitating economic development, and enhancing national security. Roads were built, connecting previously isolated regions, and the Trans-Iranian Railway, a monumental undertaking, began to crisscross the country, linking the Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea. This railway, often cited as a symbol of Reza Shah's determination, was entirely funded by Iranian taxes, a testament to the nation's newfound economic autonomy. Beyond transportation, the government invested in establishing modern industries, setting up factories for textiles, sugar, and cement. Educational reforms led to the establishment of new schools and, crucially, the University of Tehran in 1934, providing higher education within the country for the first time. These projects, while often implemented with a heavy hand, were instrumental in reshaping the physical and social landscape of **1930 Iran**, reflecting a profound commitment to progress and self-reliance.Economic Shifts: From Capitulations to Control

The economic landscape of **1930 Iran** was undergoing a significant overhaul, reflecting the nation's burgeoning independence. A crucial turning point came in 1928 when the remaining capitulations were abrogated. These capitulations, a relic of 19th-century imperial dominance, had granted foreign nationals extraterritorial rights and privileges, severely limiting Iran's sovereignty. Their abolition was a powerful statement of national self-determination. Following this, Iran asserted its own right to fix customs duties, a fundamental aspect of economic autonomy. However, despite this newfound power, the government never enacted protective tariffs to truly nurture Iran's infant industry. This decision, or lack thereof, meant that nascent local industries faced stiff competition from more established foreign goods, hindering their growth potential. A further significant development occurred precisely in 1930, when a government act established a foreign exchange control. This measure was a direct response to the global economic turmoil of the Great Depression, which severely impacted international trade and currency stability. By controlling foreign exchange, the Iranian government aimed to stabilize its economy, manage its reserves, and direct financial resources towards its ambitious modernization projects. This move, while necessary for economic stability in a turbulent global environment, also centralized economic power further within the state, influencing the trajectory of Iran's financial system for decades to come.A German Connection: Opportunity and Influence

The period between 1930 and 1941 saw a curious and significant influx of German civilians into Persia (Iran). After the First World War, at the time of the Great Depression in Europe, and with the rapid development of infrastructure projects in Iran, many young and talented German civilians considered Persia (Iran) as their land of opportunity. They were engineers, technicians, architects, and specialists, drawn by the prospect of employment and the chance to contribute to a nation actively building its future. Settling all around the cities and in the rural areas, including various territories, these Germans played a tangible role in the construction of roads, railways, and factories, becoming an integral, albeit temporary, part of the Iranian workforce. This presence was not merely economic; it also fostered cultural and educational exchanges, as German schools and cultural centers were established. The relationship was complex, rooted in mutual interests, with Iran seeking technical expertise and Germany looking for economic opportunities and strategic alliances in a region increasingly vital to global power dynamics.The Enigma of German-Iranian Relations

Despite a row of scholarly studies, the relationship between Reza Shah's Iran and National Socialist Germany has not been fully explored, remaining a subject of considerable historical debate. The "Data Kalimat" highlights that exploring this issue requires focusing on relations between Germany and Iran during three distinct moments. First, the period from 1918 to 1928 saw the working out of a new relationship after the First World War, as Germany sought to re-establish its international standing and Iran asserted its independence. This early phase was largely characterized by economic and cultural cooperation, with Germany often seen as a less imperialistic alternative to Britain and Russia. However, the 1930s introduced a new layer of complexity. The global parameters of Iranian history are highlighted through an examination of local developments in the 1930s and their interaction with the expansionist aims of National Socialism. As Nazi Germany rose to power, its interest in Iran grew, viewing it as a potential strategic ally against the Soviet Union and a source of raw materials. While Iran officially maintained neutrality, the increasing German presence and ideological overtures from Berlin created a delicate diplomatic balance for **1930 Iran**, which sought to leverage German technical assistance without becoming entangled in European power struggles. This intricate dance of diplomacy and economic cooperation would ultimately lead to significant challenges for Iran as World War II approached.Unveiling Society: Cultural Transformations

Beyond economic and political reforms, **1930 Iran** witnessed profound social and cultural transformations, particularly impacting the lives of women. Reza Shah's modernization drive extended to societal norms, often through forceful decrees. One of the most controversial and far-reaching was the "unveiling" (Kashf-e Hijab) edict, implemented swiftly and forcefully. This decree banned all Islamic veils, including the hijab and chador, in public spaces. The government's rationale was to promote Westernization, gender equality, and a modern national identity, believing that the veil was a symbol of backwardness and an impediment to progress. The implementation of this policy was met with mixed reactions. While some women, particularly from educated urban elites, embraced the freedom from the veil, many others, especially in more traditional and rural areas, found it deeply distressing and a violation of their religious and cultural identity. Women's attire, and specifically their hair, became a constant point of scrutiny, reflecting the state's pervasive control over personal life. This edict profoundly changed how women appeared in public and interacted with society, creating a lasting legacy of debate and division regarding women's rights, religious freedom, and the role of the state in personal matters, a legacy that continues to resonate in Iran today.Echoes from the Earth: The 1930 Earthquake

Amidst the whirlwind of modernization and social change, **1930 Iran** was also struck by a devastating natural disaster. On May 6, 1930, at 07:03:26 local time, a powerful earthquake with a magnitude of 5.4 mb (moment magnitude) rocked the region. The epicenter was located approximately 15 km (9.3 mi) from a significant population center, likely causing widespread damage. The human toll was catastrophic: up to 3000 people were killed. This tragic event served as a stark reminder of the challenges faced by a nation striving for progress in a geologically active region. The immediate aftermath would have seen immense suffering, loss of life, and destruction of infrastructure, including homes, public buildings, and nascent industrial facilities. While the "Data Kalimat" does not specify the exact location, such a high casualty count indicates a densely populated area was severely affected. For a government focused on building a modern state, a disaster of this magnitude would have diverted resources, tested administrative capabilities, and highlighted the vulnerability of even the most ambitious development plans to the raw power of nature. The earthquake was a somber punctuation mark in a decade otherwise defined by human-driven transformation.Unearthing History: Archaeological Endeavors

While **1930 Iran** was focused on building its future, it also looked to its past through significant archaeological endeavors. The "University Museum's Damghan Project" was a prominent example of international collaboration in uncovering Iran's rich heritage. This project involved excavating Tepe Hissar, a crucial archaeological site near Damghan in northeastern Iran. Tepe Hissar yielded invaluable insights into the prehistoric and early historic periods of the Iranian plateau, revealing layers of continuous occupation dating back thousands of years. The excavations unearthed a wealth of artifacts, including pottery, metalwork, and architectural remains, shedding light on ancient civilizations and their interactions. A particularly significant discovery at Tepe Hissar was the Sasanian Palace, offering a glimpse into the grandeur and architectural prowess of the Sasanian Empire (224-651 CE), one of ancient Iran's most powerful dynasties. The meticulous work of archaeologists at sites like Tepe Hissar was crucial for understanding the deep historical roots of Iran, providing a scientific basis for the nation's proud cultural heritage. The "closing the Tepe Hissar excavations" marked the completion of a phase of intensive research, but the findings continued to inform scholarly understanding for decades.From Berlin to Basra: A Global Perspective on Archaeology

The phrase "From Berlin to Basra to Fara" hints at the broader international context of archaeological work during this period, particularly in the Middle East. While the specific connection to Tepe Hissar isn't explicitly detailed in the "Data Kalimat," it suggests a network of archaeological expeditions emanating from major European academic centers (like Berlin) and extending across the ancient Near East, reaching as far as Mesopotamia (Basra, Fara being ancient Sumerian city). This global perspective underscores that the archaeological work in **1930 Iran** was not isolated but part of a larger, interconnected scientific endeavor. European institutions, with their established academic traditions and funding, often led these expeditions, collaborating with local authorities and nascent Iranian archaeological departments. This collaboration, while sometimes fraught with colonial undertones, significantly advanced the understanding of ancient civilizations in the region. The findings from sites like Tepe Hissar contributed to a global body of knowledge, enriching the understanding of human history and cultural development, and placing Iran firmly within the grand narrative of ancient world civilizations.Industry and Innovation: A Nascent Industrial Scene

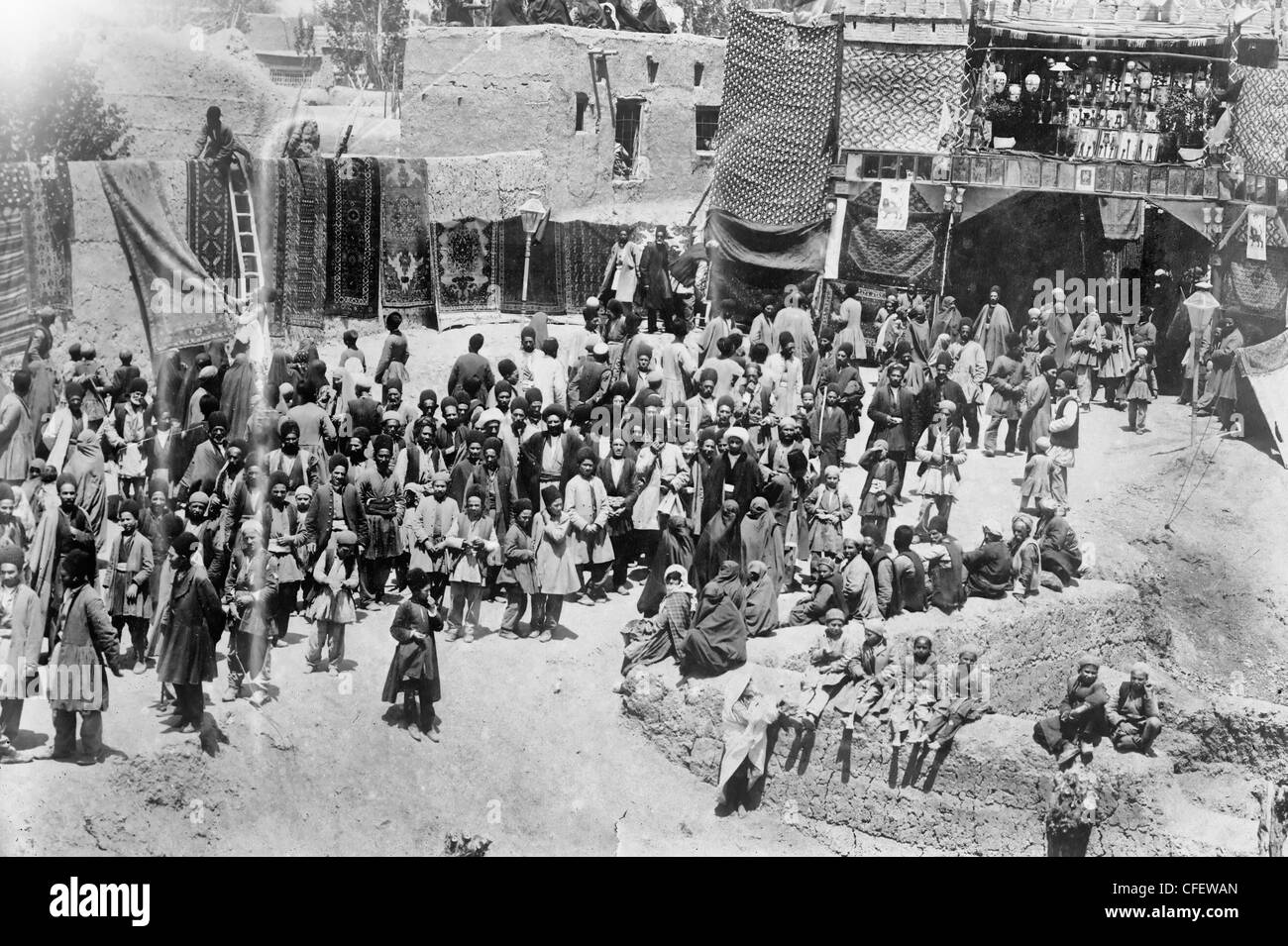

The industrial landscape of **1930 Iran** was still in its nascent stages, despite the government's push for modernization. Prior to the 1920s, traditional crafts (q.v.) dominated the industrial scene. These crafts, ranging from carpet weaving to metalwork, were deeply embedded in the cultural and economic fabric of the country, reflecting centuries of artisanal skill. However, they operated largely on a small scale and with traditional methods. Despite a growing interest in industrial modernization after the 1870s, the role of industry remained very limited in the economy at the turn of the 20th century (Issawi, 1980). By the 1930s, Reza Shah's government was actively trying to change this. The establishment of factories for sugar, cement, and textiles marked a deliberate effort to shift away from reliance on imports and develop a domestic industrial base. However, these were early days, and the scale of industrialization was modest compared to more developed nations. The lack of protective tariffs, as mentioned earlier, also meant that these nascent industries struggled to compete with established foreign goods. Nevertheless, the decade laid the foundational stones for future industrial growth, signaling a strategic shift towards a more self-sufficient and modern economy for **1930 Iran**.The Communist Movement and Global Parameters

The 1930s were also a significant period for the history of the Iranian communist movement, which is an integral and important part of the modern history of Iran and international relations. While the Pahlavi state was authoritarian and suppressed political dissent, communist ideas, influenced by the Soviet Union, found adherents among intellectuals, workers, and some segments of the military. The global parameters of Iranian history are highlighted through an examination of local developments in the 1930s and their interaction with the expansionist aims of National Socialism. This interaction created a complex geopolitical dynamic. On one hand, the communist movement in Iran was a domestic force, advocating for social and economic justice, often at odds with Reza Shah's autocratic rule. On the other hand, the rise of National Socialism in Germany, with its anti-communist stance, created an interesting tension. While Germany sought to cultivate relations with Iran to counter Soviet and British influence, the presence of a burgeoning communist movement within Iran added another layer of complexity to these interactions. The 1930s saw the suppression of communist activities within Iran, but the ideological battle between communism and fascism, played out on a global stage, inevitably cast its shadow over Iran, influencing both domestic policy and foreign relations.Legacy of a Pivotal Decade: 1930s Iran

The decade of the 1930s, particularly the year 1930 itself, stands as a testament to Iran's determined march towards modernity under Reza Shah Pahlavi. It was a period of intense national identity formation, symbolized by the official adoption of "Iran" over "Persia." Economically, the abrogation of capitulations and the establishment of foreign exchange control asserted the nation's sovereignty, even as the industrial base remained nascent. Socially, the controversial unveiling edict dramatically reshaped public life for women, reflecting a top-down approach to cultural transformation. The extensive infrastructure projects, from railways to factories, laid the physical groundwork for a modern state, often with significant German technical assistance. This German connection, however, was a double-edged sword, reflecting the complex geopolitical maneuvering of **1930 Iran** amidst rising global tensions and the expansionist aims of National Socialism. Even a devastating earthquake could not halt the relentless pace of change, as archaeological endeavors simultaneously unearthed the nation's ancient past. The 1930s were a crucible of change, where a nation sought to forge its own destiny, grappling with internal reforms, external pressures, and the enduring echoes of its rich history.Conclusion

The year **1930 Iran** was far more than just another point on a timeline; it was a nexus of transformative forces that profoundly shaped the nation's trajectory. From the deliberate renaming of a country to the ambitious economic and social reforms, and from the intricate dance of international relations to the devastating impact of natural disasters, this period solidified Reza Shah's vision for a modern, independent Iran. The foundations laid during this decade, both literally and figuratively, would continue to influence Iranian society, politics, and economy for generations to come. We hope this exploration has offered you a deeper understanding of this pivotal era. What aspects of **1930 Iran** do you find most compelling? Share your thoughts in the comments below! If you're interested in delving further into Iran's rich history, be sure to explore our other articles on the Pahlavi dynasty and the broader context of Middle Eastern modernization.

Persia/Iran- 1930 Mint Full Set | Middle East - Iran, Stamp / HipStamp

Empire of Iran, circa 1930 : AlternateHistory

Visit of Ahmad Shah Qajar (1898-1930) to Urmia, Iran. Ourmiah, Persia